Ryan Velez

Practical Openings Approach

This post is for people who need to learn openings, but struggle.Three Parts of this Article

Part 1

Why are openings so difficult?

Part 2

Practical opening advice

Part 3

Opening study resources

NOTE: I make no apologies for the length of this article. It is full of a lot of very good, not often discussed ideas. I figure anyone who is serious will read the whole thing. :-)

Part 1 - Why are openings so difficult?

Building an opening repertoire feels like building a brick house with mortar that never dries. When I taught myself how to build patios, one of the critical things I did before starting was research the most common ways failure occurs. Understanding these common problems gave meaning to the steps I took to build the patio.

Chess is the same way, and we will apply this lesson to openings. Let’s look at the reasons openings are difficult to learn, and what the points of struggle are within those reasons.

Difficulty 1 - Memorization

Memorization is a huge requirement of opening prep. Anyone stating otherwise is saying “Don’t use part of your brain for chess.” Memorization is essential, and there will be a time when you must sit down with intent to memorize moves. Top players often use the phrase “When you build an opening repertoire...” The moves you memorize are the bricks of your metaphorical opening repertoire house. The more moves you memorize, the larger your potential house can be.

Point of Struggle

Every person has a different capacity for memorization. Some of it is ability, and some of it is proper memorization technique. Age is a factor, as we all know, but proper technique can compensate for age a great deal, as we will see.

Difficulty 2 - Overwhelming Information

The 9 million possibilities after move 3 succinctly quantifies the task of learning openings, and every learner’s dread deepens when they realize most openings go past move 10. But most people do not reflect on what these numbers mean. Most chess moves are bad, and the vast majority of moves are helpful for the opponent. Based on this alone, it is correct to say that playing chess well means helping the opponent as little as possible.

Point of Struggle

The number of possible positions in the opening acts like a paralytic venom which stagnates a player’s growth until they find the antidote. Many people fail to realize that openings are paths through the swamp of infinite possibilities. Openings are the antidote. But students who do not wish to memorize moves still understand the importance of the opening, so they persist in trying to find clever ways to make the task more manageable, and begin asking questions like...

- Is there a simple way to learn openings?

- What openings are best?

- What openings do you recommend?

- Are opening “Systems” any good?

- Are there simple openings?

- Should I bother learning “The Sicilian”?

- How many openings do you (me) know?

Sticking with our metaphorical house, it is our job as improvers to establish a solid foundation within the network of overwhelming information. As you will learn, a solid foundation begins with two openings, and branches out from there. Rest assured, you do not need to know every opening, and you do not need a response to every possibility.

Difficulty 3 - Understanding Moves

The main skill we’re all trying to develop, even outside of openings, is how to understand moves. Memorizing moves without understanding them means you will score poorly against higher rated opponents, and it is those people you must beat to demonstrate improvement.

Point of Struggle

More money is spent on learning the opening than any other part of chess. You can spend infinite money on chess opening books, courses, software, and coaching. But no amount of money spent on opening materials is guaranteed to improve your ability to play the opening. And without discretionary income, you’re simply forced to stare down the 9 million positions on your own.

If memorized opening moves are the bricks of an opening repertoire, then understanding each move is the mortar. With a strong foundation, and enough bricks and mortar, you will be able to build an opening repertoire with confidence, and succeed at playing through the opening most of the time.

Difficulty 4 - Navigating Transpositions

Once you learn openings, especially if you are a 1.d4 player, you will discover how transpositions work. Transpositions occur when the same position is reached through a different order of moves. Here is a simple example:

Base Position 1 - French Defense: Exchange Variation

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.exd5 exd5 4.Nf3 Nf6

Transposition 1 - Queen’s Pawn Game <—> French Defense

1.d4 e6 2.e4 d5 3.exd5 exd5 4.Nf3 Nf6

Transposition 2 - The Russian Game <—> French Defense

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nf6 3.Nxe5 d6 4.Nf3 Nxe4 5.d3 Nf6 6.d4 d5

The first two examples show an equal number of moves, and a very slight transposition from the queen pawn game into the French Defense Exchange Variation. The third example shows the same position being reached as the first two, but it begins very differently and takes an additional 2 moves by both players to reach the same position. Next is a more complex example:

Base Position 2 - Nimzo-Indian Defense

1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. e3 c5 5. Bd3 d5 6. Nf3 O-O 7. O-O cxd4 8.exd4

Transposition 1 - Panov Attack

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. exd5 cxd5 4. c4 Nf6 5. Nc3 e6 6. Nf3 Bb4 7. Bd3 O-O 8. O-O

Transpositions have 2 major purposes:

- The avoidance of specific lines of play (or to avoid specific openings)

- To confuse opponents, who often only memorize chess moves

For example, in the French Defense transposition that began with 1.d4, white could be simply avoiding the Sicilian Defense by playing d4 before e4. When the opponent played 1...e6, white felt fine with a French Defense and responds with 2.e4. Likewise, in the Nimzo-Indian and Panov Attack openings, a player who only memorized the black side of the Nimzo-Indian Defense might not notice they are in the same resulting position if the game began with e4 as in the Panov Attack.

Point of Struggle

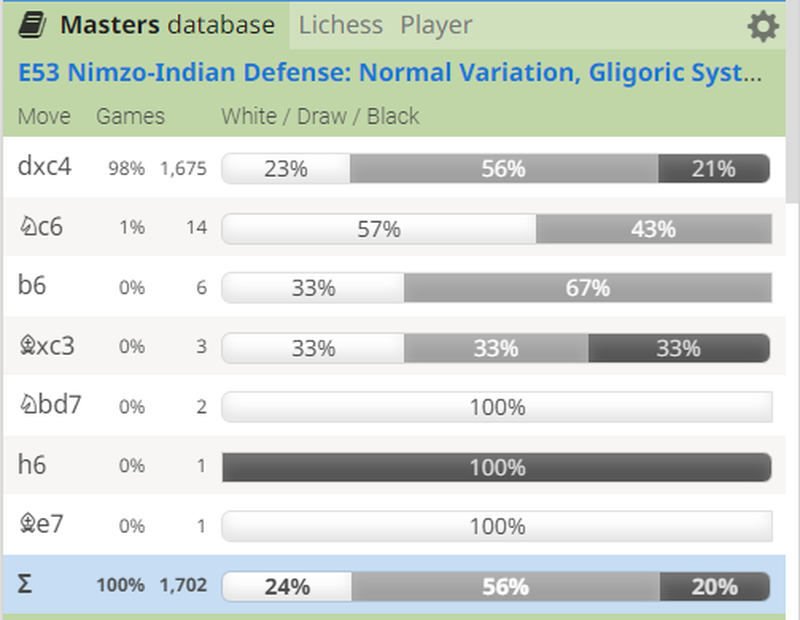

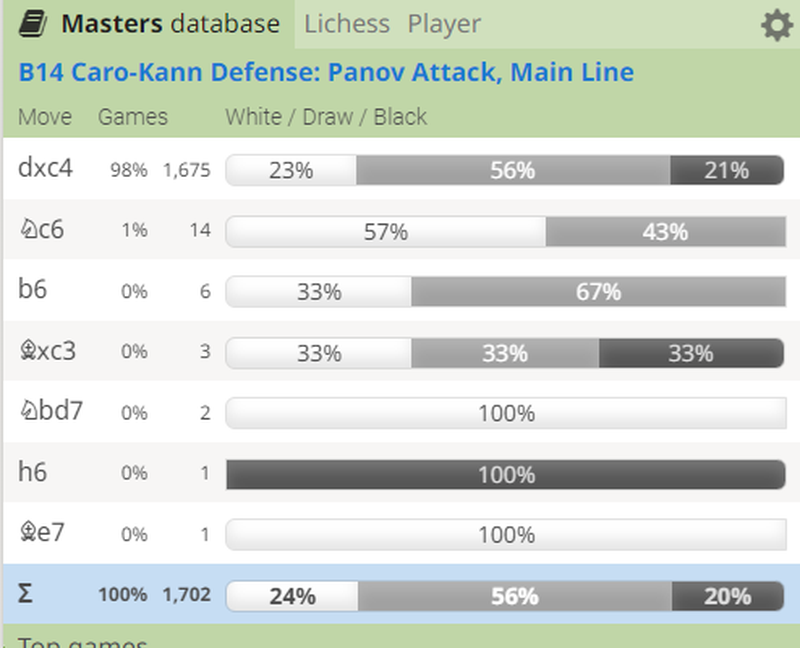

Transpositions are useful, but can make learning, and implementing, openings difficult. Failing to recognize transpositions means you have prioritized memorization over understanding of moves, and positions. It also means you have not looked at enough examples of the openings you wish to play. Chess books, and videos, often point out these transpositions. However, databases are more subtle about it, or often fail to point them out. For example, check out these images from the Lichess database:

The stats are the same for both openings, but the names of the openings, and their ECO codes (E53 and B14) remain unchanged. Therefore, if you did not know about these changes, you may not fully grasp a transposition occurred. But the database does handle these appropriately because both of these openings promote, and avoid, different lines of play. So, while the resulting positions are the same, there were many points either player could have veered away.

Difficulty 5 - Tactics / Traps

The difference between a trap and a tactic is a trap requires you to make a bad move, damaging your position, to set up an unforced tactic. Trap lines are always based on hope, and hope chess is not a winning strategy most of the time. Tactics only require observation to exploit, and cannot be forced until an error occurs. Traps take the approach that you can set up a tactic, and this is why trap lines are tempting, but fail against seasoned opponents.

Point of Struggle

There are 3 failures at this stage:

- Not learning tactical lines.

- Embracing trap lines.

- Not investigating intuitive-looking responses

The first two reasons, and their solutions, are evident: learn those lines. But the third one is where, I believe, most people fail to truly understand an opening. You must research reasonable looking moves that aren’t covered by your opening software, book, lecture, or coach. In chess, many moves appear reasonable and intuitive, but wreck the position for one side or the other. Here is a simple example:

I never read about this 9.e4 move in a book or anything, I just wondered “What happens if 9.e4?” Initially, it seemed reasonable, and I am certain I have played this move as white before in blitz games. But the chess engine shows how terrible it is for white. With just a brief glimpse into the future, you can see how this move allows black all the attacking chances, while white’s pieces are entirely passive.

I cannot emphasize enough how critical it is for you to investigate reasonable moves that are not part of an opening you are learning. Understanding why those moves fails strengthens your understanding of the chosen opening.

Difficulty 6 - Analysis of Openings seems Unending

The color gradient below is a visual analogy for how difficult it can be to know the exact moment when an opening transitions into the middlegame. Therefore, people are often left wondering when the opening ends? Can you pick out the exact point where the blue turns to orange? This visual analogy would be even more difficult if I used yellow and orange. Openings are the same way, some openings have a harder, more clear transition. Others, like yellow and orange, are more seamless and difficult to pin down.

Point of Struggle

People fixate on when the opening ends, and they want, desperately, a number that applies to all openings. But no such number exists, and anyone claiming as much is exercising chess-bullshido. While it is frustrating to know this question does not have a universal answer, it is freeing in that we don’t have to worry about the answer, either.

Difficulty 7 - Interpreting databases

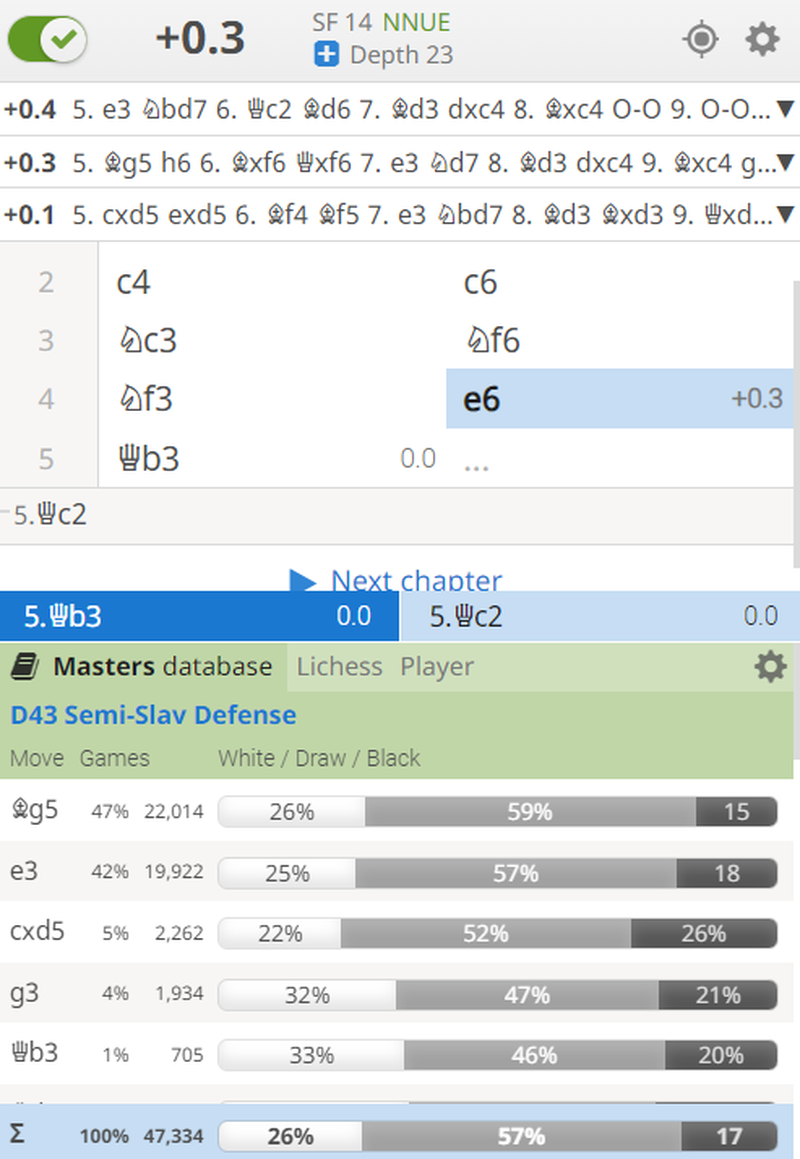

Information on openings has never been more freely available. Openings databases have revolutionized how people learn openings. The information they offer is powerful, but unexplained, and requires learners to interpret the data themselves. Consider this example from the Semi-Slav Defense:

I didn’t let the engine run for a long time. However, what we have are 3 engine moves, and as I write this article, Lichess has 12 moves in its Master Database:

5.Bg5

5.e3

5.cxd5

5.g3

5.Qb3

5.Qd3

5.Qc2

5.Bf4

5.a4

5.Bd2

5.b3

5.c5

5.Qd3 and below are not pictured, but the Lichess database has them. Not all of these moves are playable, like 5.b3. But the majority of them are decent enough. I did find a move that wasn’t in Lichess’ database, but it did have 4 follow up games: 5.Qa4. It is a viable move that leads to equality, but it is not super studied.

My point is should someone stick to playing only the listed moves, or try to find new moves? Should someone consider playing moves with a huge draw percentage or only moves that offer a win percentage? What percentage is worth playing and which are worth avoiding? Should I only play moves where the chess engine and the database are in agreement? Database interpretation is up to you, and at the end of the day, you must select moves to play, and be confident they are decent moves.

Point of Struggle

Many people conclude that making the moves with the best percentages, at all times, is the way to go. Like memorizing moves, you will have some success with this approach; however, this approach ignores several things:

- Novelties

- Alternative playable moves

- Draw lines

Novelties can wreck opening repertoires, and novelties are most notably not in databases yet. In Difficulty 6, I recommend investigating intuitive-looking moves. Doing so will often produce a novelty, or at the very least offer an alternative way to play, because playing the same way all the time can make you predictable. Knowing drawish lines can be helpful, too, in situations where you only need a draw.

But the biggest issue with databases is it heavily reinforces memorization, and de-values understanding of moves when used incorrectly (and since no training is offered, most people use databases incorrectly in one way or another).

Difficulty 8 - Numerous Opening Options

There are so many opening options, learners and improvers do not know where to begin. Opening names can be exciting and confusing, too. There are attacks, defenses, gambits, counter-gambits, and systems. There are mainlines, variations, subvariations, trap lines, and so forth, too. Confusion further sets in when they learn “King’s Indian Defense” is a defense, but it attacks on the kingside... so is it an attack or a defense?

Understanding how openings are classified can help you understand what kind of opening you might wish to play. Check this link out:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclopaedia_of_Chess_Openings

The Encyclopedia of Chess Openings gave the world ECO codes, which are those 3 digit codes that range from A00 - E99. One useful bit of information that isn’t apparent, and this is a very loose rule, is that the ECO codes are organized by pawn structure. Open, Semi-Open, and Closed each have implications about pawn structure. As do “Flank Openings” and “Indian Openings.”

Point of Struggle

Rather than pick a starting point, people spend a long time surveying around, asking questions, and never committing to learning an opening. My advice is always the same: pick something, a build from there.

Part 2 - Practical Opening Advice

Step 1 - Select Two or Three Related Openings

Companion Openings

Schema Theory, pioneered by Sir Frederick Bartlett in 1932, discusses how people organize knowledge to create mental frameworks, which helps create expectations of certain experiences. For example, you have a mental image of what a restaurant will be like, even before going into a new one.

In the Wikipedia link, the first paragraph has an important note for the chess learner:

Schemata influence attention and the absorption of new knowledge: people are more likely to notice things that fit into their schema, while re-interpreting contradictions to the schema as exceptions or distorting them to fit.

When learning new knowledge, like an opening, it is easier if it fits into a schema you already know. This is why I recommend learning 2 openings at once (or if you wish to use the “bridge opening” route, you can learn 3 openings at once). Essentially, learning openings in pairs is a good idea so long as those openings have enough similarities to make comparisons, and we will call these openings Companion Openings.

However, note the second part of the Schema Theory quote above that suggests people will distort information to fit it into the schema (often inappropriately). This happens in chess when people assume a move can occur at any moment during the opening. So, be very careful not to make such an assumption.

Companion Openings can be identified in the following ways:

1. They have similar pawn structures and/or piece placement.

2. Transpositions exist between the openings.

3. The openings have similar strategic goals.

Here is a list of companion openings I have discovered over the years (note: these openings all share similarities, but are in fact different, and it is the similarities that can help you have a small boost in learning them):

- Italian Game, Four Knights, Scotch Game, Ruy Lopez

- Tarrasch Defense, French Defense, Caro-Kann Defense

- Queen’s Gambit Accepted, Queen’s Gambit Declined, Slav Defense, Semi-Slav Defense

- Nimzo-Indian Defense, Bogo-Indian Defense, Queen’s Indian Defense

- Nimzo-Larsen Attack, Owen’s Defense

- Modern Defense, Pirc Defense, Philidor Defense, Russian Game

Each of these match ups have similarities in both pawn structure and piece development. But of course, as they are all different openings, differences exist. Companion Openings exist within opening variations as well:

- Dragon Sicilian, Accelerated Dragon Sicilian, Hyper-Accelerated Dragon Sicilian

- Najdorf Sicilian, Lowenthal Sicilian, Lasker-Pelikan Sicilian

- Kan Sicilian, Taimanov Sicilian

The Dragon Sicilian defenses are separated simply by when black decides to play ...g6 and whether or not they play ...d6 or hold the pawn back to play ...d5 in one move. The Najdorf, Lowenthal, and the Lasker-Pelikan Sicilian Defenses are concerned with the d6 and e5 pawn structure for black. The Paulsen Sicilian, Kan Sicilian, and Taimanov Sicilian all have e6 as a move, which sets them apart from the Dragon and Najdorf Sicilians.

Bridge Openings

I also recognize openings that link two seemingly distant openings together:

- King’s Indian Defense and the Najdorf Sicilian are bridged by the Benoni Defense.

- King’s Indian Attack and the Nimzo-Larsen Attack are bridged by Queen’s Gambit.

- The Scandinavian sits in between the Caro-Kann and French Defense.

Bridge openings overlap less on ideas and moves than companion openings, but find connections between strategic concepts. For example, the French Defense, Caro-Kann, and Scandinavian all approach the d5-square differently. However, the French Defense and Caro-Kann have similar pawn structures in their respective Advance Variations.

In the case of KID, Najdorf Sicilian, and the Benoni Defense, I have always felt that the Benoni Defense tries to bring together benefits of KID on the kingside and the Najdorf on the queenside. However, the Benoni is not a super great opening and my discovery has only led to losses with the Benoni. But my understanding of why the Benoni is not the greatest opening to play comes from my understanding of King’s Indian Defense and the Najdorf Sicilian, and that knowledge is still worthwhile, even though I do not play the Benoni.

Mirror Openings

Mirror Openings are not “Symmetrical Variations” of openings, but rather when you attempt to play the same opening structures for white and black. Here are some examples:

- Bird’s Opening and The Dutch Defense

- King’s Indian Attack and King’s Indian Defense

- Nimzo-Larsen Attack and Queen’s Indian Defense

- Sicilian Dragon and the English Opening

If you investigate these, you will see the pawn structure and development are similar for each in some respects, and different in others. All mirror openings have to take into consideration that when playing white you’re up a move, and when playing black you’re down a move. The Sicilian Defense, for example, is a counter attacking opening. But no one sees the English Opening as a counter attack even though it implements similar ideas and themes.

Conclusion

However you choose to select openings, have some methodology to fit them together. Eventually, when you have experienced enough openings, you won’t need to do this anymore. But if you are just starting out, or you want to redo your repertoire, pairing openings together is a very helpful idea.

Step 2 - Learn the Opening’s History

When did the opening first make its debut?

Learning about an opening’s evolution from its inception to modern day versions of itself is instructive, and fun. The best way to find its beginnings is to use a “classical games database.” Both ChessGames.com and ChessTempo.com have free databases, but others exist. ChessBase maintains the gold standard of databases if you have the funds. ChessGames.com allows you to search for players, a range of dates, etc... ChessTempo allows you to do position searches, and has a better layout for perusing games.

What I like to do is copy the PGNs from either site (or download them), and paste them into a Lichess study chapter by chapter. Once you figure out when an opening had its debut, you can move on to the next part of this step.

Through the Decades

Look at games in that opening over the decades. Don’t just look at victories: look at wins, losses, and draws. I recommend clicking through the games and just enjoying them initially. When you find games that stand out, for one reason or another, save those PGNs and put them into a study in chronological order (or some approximate order).

Some people may struggle to know which games are important to save and review. Here are some things to consider:

- The game is played by top level players of that era.

- The event where the game too place can be important (like a World Championship).

- Games that have a consistent theme (like black’s Rxc3 move in the Dragon Sicilian).

- Games that simply interest you.

All you need is 3 to 5 games from each decade that give you a good sense of how the opening was played. Don’t pick the first 5 games you find (unless there are only 5 games). Peruse through the games, get a sense of what looked common, and decide on some games from there.

Your goal is to see how the opening changed over time. One example I can offer you is looking at when ...b5 was played in the Najdorf Sicilian. Overtime, this changed a lot as early examples of pushing b5 very quickly have been proved to mostly not be a good idea.

Identify Main Practitioners

ChessGames.com lists common practitioners on their site, which is helpful. Other databases may be able to help you with this too. While it is less common to see modern grandmasters stick with an opening throughout their career, finding a player who regularly implements an opening you’re learning is helpful — just make sure this player is at least an international master or a grandmaster.

Once you know the main practitioners of an opening, check out their games!

Step 3 - Learn the Opening

Understand Moves

Remember, the purpose of an opening is to get you to a playable middlegame, which means having a strategic goal or two, and piece activity. If you start the middlegame with tons of passivity, you’re going to have a difficult game. But understanding moves can be difficult, and this is when people start spending money on chess. Here are some tips for understanding moves that aren’t as common knowledge:

Tip 1 - Threads of Familiarity

Whether due to a transposition, a specific required moment, or if an error is made, many openings have moves that are played at different moments in time. For example, in the Classical Sicilian Defense, white can play the move f4 at many different points. Studying moves like this can be important. Here is an example:

As you can see, the move f4 can be played at several different moments within, and just before, the Classical Sicilian. I call this “Threads of Familiarity” because a thread of logic can be created between each moment f4 could be played, and understanding when it is good, mediocre, or bad helps you understand the positions you get into much more deeply.

However, the Threads of Familiarity idea can also be applied between different, but related, openings, too. For example, the role of the f4-pawn in the Closed Sicilian:

The f4-move can be played for very similar reasons in both scenarios. However, in the Closed Sicilian, f4 seems to be a mistake more often because white has no real need to play the move until their development is is completed, and aiming at the light squares in the center.

I will note that f4 is a common move in the Closed Sicilian, but there is less flexibility with when it can be played when compared to the Classical Sicilian due to white castling on the queenside.

Tip 2 - Opening Principles

Opening principles can explain moves, too. Because so much is written on opening principles, I won’t elaborate here. However, I will note that understanding when an opening principle can be broken is important for understanding the moves in openings. Here are some examples of what I mean:

1. Alekhine’s Defense moves the same piece multiple times.

2. The Scandinavian Defense brings the queen out early.

3. French Defense: Advanced Variation develops a knight to the edge (Nh6), moves the queen out early (Qb6), and moves the same piece multiple times (Ng8—>Nh6—>Nf5).

There you see two openings that violate an opening principle, and then a third that violates the same principles, and develops a knight to the edge; yet, all three are reputable openings. Broken opening principles often teach us about the opening in question.

Tip 3 - The 3 Layers of an Opening

In my Layered Analysis article, I propose a way to break down chess games into their understandable components. When studying an opening, you can definitely break the opening down into layers, just like you can do with a whole game. There are 3 layers within every opening:

- The Tactical Layer

- The Positional Layer

- The Strategic Layer

The Tactical Battle

The tactical battle happens in the minds of the players, until someone overlooks a tactic and the opponent exploits it on the board. The tactical layer includes any and all of the following:

- Tactics and threats

- Sidelines that include tactics

- Trap lines

- “Intuitive-but-bad” moves with tactical refutations

If you lose the tactical battle, then you come out of the opening with less material, or with a compromised situation that may result in material loss in the near future.

The Positional Battle

The positional battle happens on the board, and is quite visible most of the time. This battle includes common chess themes such as

- Who controls a key file?

- Who is able to dominate an important square?

- Whose minor pieces are more useful?

- Who has a protected passed pawn?

- Does white end up with an isolated pawn?

- Is black’s king unable to castle?

There are too many positional elements to list, but many openings often harmonize their pieces around a positional advantage of some kind. It should be noted that not every opening concerns itself with a specific positional advantage, and piece activity is usually more valuable than a positional plus, especially very wide open games, but it is common enough that doing a positional layer of analysis is not a bad idea.

The Strategic Battle

The strategic battle is often the middlegame benefits (and sometimes endgame benefits) an opening is trying to obtain. If one player wins the strategic battle early on, then it means any plan created by their opponent will inevitably run out of steam, with proper play. Strategic battles can include things like

- An early passed h-pawn (see Semi-Slav Defense Accepted: Botvinnik Variation)

- The bishop pair

- Knight vs bishop endgame with pawns on one side (usually good for the knight)

- A weakened light-square color complex

These kinds of advantages take time to realize, and wouldn’t be considered “positional advantages,” as a positional advantage sits on the board. A strategic advantage takes many moves to organize it into an advantage. Having a passed h-pawn on move 10 isn’t really a big deal most of the time, but by move 49 it could be a massive advantage.

Tip 4 - Kingside and Queenside Development

I have always found it very interesting to pay attention to how the kingside develops and how the queenside develops. Ideally, both sides should develop in a coordinated fashion. But I have found that many openings develop one side, then the other. Paying close attention to how both sides deploy pieces, and how they coordinate, can teach you why a move is made, and when.

While it is not a hard and fast rule, once you see how both sides develop the kingside and the queenside, the opening is typically over. Again, this is not always true, but often true. For example, white can put their knight on c3, and that is development. However, if that knight is meant to go to g3, like in some Ruy Lopez variations, then the opening isn't really going to be complete until that knight gets into its intended position.

Tip 5 - Decide when to stop studying an opening line

It can be difficult knowing when to stop studying a specific opening. There is no universal answer, but here is a practical answer for now:

- If the kingside and queenside are developed, and you have a plan, stop studying the line.

- If the evaluation spikes, figure out why, then stop studying that line.

- If a line is avoidable and you don’t like it, stop studying it.

- For 99% of people, studying the opening past move 15 - 20 isn’t super helpful.

If you don’t have a place to stop studying openings, you will fatigue yourself. It is better to review, and understand, 10 lines of play that are 10 moves deep then to study 1 line 25 moves deep. The chances of someone playing every move you know is very rare outside of mainline openings, so don’t pressure yourself.

When discussing studying openings, I also like to offer 3 Zones of Evaluation that can guide you on when to stop studying:

- The Zone of Comfort

- The Zone of Discomfort

- The Zone of Equilibrium

The Zone of Comfort

When you conclude your study of an opening line, you should feel comfortable with that position. If you feel uneasy, it is because you do not understand your position. Feeling comfortable out of the opening is helpful, but it does have some psychological disadvantages during a live game:

- You let your guard down more easily

- A comfortable situation doesn’t mean it is a safe situation

- If you have reinforced a bad habit, then a bad position can feel comfortable

But in general, if you get into a comfortable position that is also a safe position, then you are playing to your strengths, and have better chances to win.

The Zone of Discomfort

After you learn an opening, if you are uncomfortable, you need to assess what is making you uncomfortable. I find most people who memorize computer moves, without understanding why the computer selected those moves, know they are in a good position, but are uncomfortable. Usually, discomfort comes from a lack of knowledge, but feeling discomfort in a game can have advantages:

- Your guard is up because you know you are uncomfortable.

- An uncomfortable situation doesn’t mean the situation is necessarily unsafe.

- Anytime you feel discomfort, you are not experiencing a reinforced bad habit

The zone of discomfort always means you are in unfamiliar territory, and will likely need to expend more energy to figure things out than normal. And while it is generally better to be in a zone of comfort, the alertness and awareness gained by being uncomfortable can aid you in winning chess games if you find yourself playing against something you have not seen before.

The Zone of Equilibrium

A lot of people believe an opening should give you an advantage, and I think this is why a lot of people, at some point, favor gambits. Gambits often have lots of trap lines and tricks that net an early-game advantage. However, you cannot do anything about how well your opponent plays, and if they play equally well, then a draw is on the horizon. If your opponent out plays you in a gambit, they are usually winning with their material plus, so be careful.

Many opening lines you study will end in equal positions, and that is ok. Don’t scoff at that, embrace it. Learning how to play equal positions is important. Most people do not play equal positions very well. Therefore, getting to an equal position doesn’t mean the game will end in a draw for 99% of chess players.

The zone of equilibrium has some interesting nuances:

- Equal positions are not usually completely safe

- Equal positions can create the time disadvantages that uncomfortable positions create

- Equal positions have a lot of invisible volatility

Equal positions are positions where any threat made has a defense. But like all things in chess, it is a skill to hold the balance in an equal game.

Step 4 - Memorize Moves, within Context

There are 2 major reasons you want to understand chess moves:

- Understanding provides context to memorized moves.

- When the opponent errs, you can figure out why, and punish their error.

I recommend a few ideas for memorizing moves:

1. Memorize key games for your opening.

2. Play through the opening repeatedly (often, with software).

3. Companion Openings

Memorizing Games

It sounds tough, but you can do it. If you play through a game enough times, and study the moves that occur in that game enough, you will very easily remember the key ideas of that game, if not the moves.

Repeatedly Play Moves

Playing through the moves manually, or with software, is the best way to memorize moves. I’ll share some more on this in the next section.

Companion / Bridge / Mirror Openings

By learning similar openings side-by-side, your mind puts both openings into context of each other. This is how neurological pathways are built, and taking advantage of that helps you learn openings more easily.

Part 3 - Opening Study Resources

Books

Chess books are an amazing resource for openings because a chess book is a titled player’s research on an opening. When you buy a chess book, you’re buying research. It saves you a lot of personal time to buy a chess book. However, there are 3 disadvantages to chess books:

- You didn’t do the research, and often the research is where you learn.

- If you cannot memorize the whole book, you aren’t “playing the opening right.”

- Authors often do not cover “reasonable moves that are unreasonable.”

Therefore, just because you have a chess book, doesn’t mean you will be given all the answers. There are always lines of play that get removed from openings books either during the editing process, due to space, or because the author didn’t think anyone would consider some reasonable looking move whose evaluation is actually bad.

If you buy chess books, I highly recommend buying from living authors for 2 reasons:

- The living appreciate your business more than the dead.

- Older openings books tend to get outdated.

I will recommend openings books / courses from 3 people:

GM Carsten Hansen

IM Cyrus Lakdawala

IM John Bartholomew

Other excellent authors exist, but I find these guys write well. Cyrus and Carsten do a lot of publishing of physical books through Everyman Chess, New In Chess, and others. John has written several courses for Chessable which are all very good. I have experience with all three of these guys. They do high quality work, and I think the world of them as chess educators. I also believe Everyman and New In Chess produce the best chess literature.

One book series, that is a little older but not out of date, is the “Starting Out” series by Everyman. Those are also excellent books for learning the beginnings of an opening, which is why these books aren’t outdated. They don’t delve too deeply into the opening, and they show you the basics. Their “Opening Repertoire” series, which is much current, is a good place to invest money once you have decided upon some openings to learn.

Videos / Streams

Opening videos / streams are the main way a lot of people are trying to learn openings. The biggest advantage to videos is most of them are freely accessible on YouTube, Twitch, etc... A lot of information can be learned, especially if you watch a live stream and can get some questions answered.

But there there are some downsides to videos:

- Non-educational videos have lots of distracting information (like on a stream).

- Most educational videos are short (to get you to watch more videos).

- Modern video creation prioritizes likes, views, and shares over content quality.

- Entertainment is prioritized over content.

Therefore, a catchy video on some crappy sideline gambit often garners tons of views when compared to something like a video titled “A deeper look into attacking the center.” A talented player can also beat lower rated players using terrible openings, and make it look good. So, beware of who is selling you openings knowledge, and how likely that knowledge is to come up in your games, and actually be useful.

Position Trainer / Lichess

One of the best pieces of software out there for memorizing openings is Position Trainer. It is low cost, and useful, but has a high learning curve. Essentially, you enter opening lines, and they are saved. Then, you can train in those lines. Do note that if you must enter your own moves, it means you must enter moves that are good, and moves you understand. The more lines you enter, the longer the training sessions go. It is very useful software.

Lichess can simulate what Position Trainer does for free on a smaller scale, with fewer bells and whistles. Basically, if you create a study, and create a chapter using the “Interactive Lesson” Analysis Mode, you can enter moves of an opening you like (and write notes about moves). The computer will automatically play the opponent’s moves for you. It is an excellent free version of Position Trainer (there is still a learning curve; for example, Lichess will not display, or play through, variations or sidelines in an Interactive Lesson — you have to make a separate chapter for each variation to make it reviewable).

Part 4 - Support Exploring Chess

My Exploring Chess article series tries to be very thorough on every topic I write about. I make no apologies for the length or depth of the articles.

If you wish to encourage me to continue, please consider supporting me.

When I get to 100 paid subscribers, it is my intent to begin doing companion videos with each article to provide more detail for people. I need 100 subscribers is a specific financial goal so I can afford to produce quality videos, not just quickly made videos.

More blog posts by RyanVelez

Resigning Strategy

This article is for anyone who wants to understand the strategy of resigning, at both low and high l…

I want to improve, but I'm busy !!!

This article is for people who want to improve but are busy, and for anyone who wants to know how to…

Plateau vs Consistency

How can you become a more consistent player?