Ryan Velez

I want to improve, but I'm busy !!!

This article is for people who want to improve but are busy, and for anyone who wants to know how to answer the question “How much time should I study chess?”Section 1

Intro

It is unhelpful to be told you don’t spend enough time doing chess. You know that, and everyone who sucks at something knows that. This advice is unhelpful, raises the barrier to entry, and turns people away like a tidal wave.

You have probably asked someone, at some point:

“How much time should I study chess?”

My answer is 10 minutes. Please, allow me to explain.

Cognitive Stamina

The only chess skill you can hone during all chess activities is Cognitive Stamina, which is the duration you can remain mentally competitive before your energy wanes. Building cognitive stamina allows you to engage chess longer, whether it is playing tournament games, online games, or studying chess for hours and hours.

Measuring Cognitive Stamina

Pick a topic: tactics, openings, middlegames, or endgames. Set a timer, and study that topic until you show signs of tiredness. Then, stop the timer. You can do this for any number of study topics to build a Cognitive Stamina profile. You can also repeat this process for the same topic, and get an average time.

I find beginner’s energy levels top out around 10 minutes. This isn’t an exact science, and certainly some people can solve tactics longer than another can study an opening. But understanding how long you can engage material is more useful to you than me saying “Study chess for 2 hours every day.”

Once you have a sense of your Cognitive Stamina, you can begin to increase it. But how?

Incremental Improvement

All players improve incrementally, whether they are a chess genius or dolt. Improvement pace varies, depending on ability, but no one escapes incremental improvement. Incremental improvement involves increasing Cognitive Stamina over time.

So, how much time should I spend studying chess?

Start at 10 minutes a day. As your stamina builds, add 10 minutes to one day per week, while keeping the rest at 10 minutes. Then, add 10 minutes to a different day each week. Continue this pattern until your life collides with chess, then scale back as needed. This pattern will allow you to

- Improve incrementally

- Build cognitive stamina incrementally

- Incrementally incorporate chess into your busy life

- Incrementally study longer.

Also keep the following 2 concepts in mind when deciding on how much time you need to study chess:

Commitment Spectrum

The amount of time you spend on chess is influenced by personal level of commitment:

- Never study chess.

- Occasionally learn a specific chess skill.

- Study chess as a hobby.

- Study chess equal to the time control of a games you wish to play.

- Study chess as a serious competitor.

Each of these tiers offers a different level of commitment, and demands more time the higher you are on the list. Consider where you are on this scale, and where you’d like to be. Then, incrementally increase your study time each day as your life permits.

Tournament Time Controls

If you wish to play in a specific tournament, you need enough cognitive stamina to play the whole event (especially if you have not entered a tournament before).

For example, if the tournament you’re considering is G/30, that means you get 30 minutes on your clock. However, your opponent also gets 30 minutes. This means the game can last for 1 hour; therefore, you will need 60 minutes of stamina to get through that game.

All tournaments have multiple rounds, and shorter time control events have multiple rounds in 1 day. Therefore, if an event has 3 rounds of 30 minute chess, you will need about 3 hours of cognitive stamina. This does not mean you need to have 3 hour long study sessions, but building up to multiple 30 minute study sessions per week would be a boon.

Section 2

The Monofocus Rule

Chess is overwhelming. Everyone quickly discovers there are 14,000 things you must do with a single move, or you are playing wrong. Learning everything all at once is difficult, and creating a list of things to learn is daunting - so don’t.

I suggest the Monofocus Rule: During study sessions, focus on one thing.

If you study for 10 minutes, or 60 minutes, narrow your study content to one specific topic. Your chances of a breakthrough are increased when you study one topic at a time because all of your energy goes into learning one concept. When you do have a breakthrough, it usually occurs when connections between learned concepts are made. Here are some topic examples:

- A single opening principle.

- One line of play in the opening.

- Solve tactics within a single theme.

- Study one specific endgame, thoroughly.

- Watch one video, and possibly more than once.

- Look over a single chess game, and make notes.

- Read one part of a book (a part can be a paragraph, chapter, section, etc...)

Other examples exist, but you get the idea. Just do one thing. As you learn more skills and concepts, doing “one thing” will appear like doing ten things to a weaker outsider. For example:

Low level Player - Studies a single opening line

Moderate player - Studies an opening line and a few related variations

High level player - Studies one whole opening

Topic Selection, and Signposts of Improvement

Topic selection can be challenging; however, you give yourself hints about what you need to study all the time. The following behaviors undercut your decision making ability, and each of these behaviors is a personal improvement goldmine:

Disliking Something

Anytime you dislike something in chess, it is a signpost for improvement:

- I dislike Queen’s pawn openings; I’m an e4 player!

- It sucks when an Open Sicilian gets turned into a Closed Sicilian

- I dislike positional chess

- I dislike draws

Consider the things you dislike about chess, and seek to learn more about those topics. Another way to think of it is everything you dislike is a potential hole in your game.

Liking Something

Fondness is another signpost for improvement:

- I like giving my opponent isolated pawns

- The queen is my favorite piece

- I like castling kingside more than queenside

- I like playing the black pieces more than the white pieces

Preferences negatively steer decision making down the wrong path. For example, if you see an opportunity to isolate an opponent’s pawn, and their resulting isolated pawn isn’t weak, then you may be making a poor decision based on a preference. It is a good idea to investigate your preferences.

Avoiding Something

Another signpost for improvement is when you avoid things in chess:

- Never playing without the bishop pair

- Never taking on pawn weaknesses

- Always castling (or never not castling)

- Avoiding mainline openings

Avoidance is another behavior that controls decision making. For example, sometimes the safest way to proceed is not to castle, but if you always castle, then you are certainly going to lose in scenarios when castling is bad for your position. Investigate the things you avoid doing.

Conscious Lack of Knowledge

Everyone has a conscious lack of knowledge. The following phrases are examples of manifestations of these problems:

- “Knight endgames are difficult.”

- “I never understand why people prefer gambits.”

- “Quiet Move tactics are very challenging.”

- “It is too difficult to read a chess book.”

Anytime you discover a conscious lack of knowledge, investigate it. Try to determine why you have trouble with it or what about it bothers you. Why have you not engaged this material before now?

Generalized Statements and Rules

People seek rules to incorporate into their personal heuristics for selecting moves. Sometimes in chess, very clear rules do exist, and we like that. The Square of the Pawn is one such example. However, generalized statements in chess are signposts of improvement:

- Rook endgames are drawish

- Bishop of opposite color endgames are drawish

- A space advantage gives you time to reorganize your pieces

- Don’t move the same piece twice in the opening

While these are all often true, it is the exceptions to these rules that are interesting. One common misconception is people learn such statements, and then apply them as a factual way to win. Suggesting Rook Endgames are drawish is often true; however, a good chess player can see the approaching rook endgame in advance, and introduce a condition that makes it a win, instead of a draw — this is especially easy to do if the opponent is lacking in knowledge of that specific rook endgame, as they won’t try to prevent the new condition from being introduced.

Generalized statements are another improvement goldmine, because it is fun to find examples of when such statements prove wrong.

Researching and Studying

Chess books, videos, tactics trainers, openings software, and all manner of chess improvement materials are examples of research being done, and compiled, for you. These materials can be studied, and learned. These materials are absolutely critical for improvement.

However, at some point, a player must learn to research answers to the questions they have about chess. This is not as scary as it sounds, and it is more fun than you think. Here is an allegory for what I mean:

I wanted to build a patio in my back yard. But, I had no clue how to do this. Nonetheless, I succeeded in doing so through research. My research consisted of about 20 hours of YouTube videos and maybe 20 online articles. No single video or article answered all of my questions, but the summation of them all answered enough of my questions to give me confidence to build the patio. Even after building the patio, I still have questions. But 5 years later, the patio is fine, with no real issues.

No single chess video, book, course, tactics trainer, or opening software will answer all of your questions. It is the summation of your efforts that will, in time, answer all your questions. Here are my favorite research tools for improvement:

- Lichess studies, Openings software, and Tablebases

- Chessgames.com

- ChessTempo.com

- ChessX databasing software

- Chess books

- YouTube

Lichess

Lichess studies can each have up to 64 chapters, and each chapter can be 1 of 4 chapter types:

- Normal Analysis - This is good for going through games using Layered Analysis

- Practice with Computer - This is good for practicing positions

- Hide Next Moves - This is good for trying to remember games

- Interactive Lesson. - This is good for practicing openings / specific positions.

Chessgames.com

Chessgames.com URLs paste into Lichess study chapters perfectly. The sizable, and free, database contains all historic chess games of note. When researching an opening’s evolution over time or a specific player, this is a fantastic website.

ChessTempo.com

Lichess’ tactics software is amazing, but one thing I like about ChessTempo.com is their section on tactics definitions and examples. It is very well done, and features more tactical nuances than most other websites. It can be very handy when trying to learn, and research, tactics.

ChessX Databasing Software

This is a new one for me, but I like the software. It is simple to use, and it can connect to your Lichess account (and pull all of your games into the database). I cannot say too much more as I haven’t fully explored it yet.

Chess Books

I read an article on Lichess a few weeks ago that said something like “Chess books don’t work.” Untrue. They are awesome, and I will likely be doing a write up on how to benefit from all chess books in the future.

YouTube

YouTube becomes more useful as you improve. YouTube is easier to use, for chess purposes, if you know a lot of bold faced chess terms such as pin, hanging pawns, opening variation names, etc...

Section 3 - Conclusion

Busy people can learn chess, too. Don’t let anyone convince you otherwise. Your progress will certainly be slower than someone who can spend multiple hours improving. 10 minutes of chess each day is 56 hours per year of study time. 10 minute increases improve that time by a lot, so pace yourself, and slowly integrate chess into your life at a level that works for you.

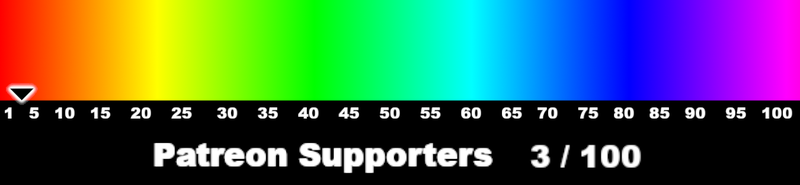

Support

My Exploring Chess blog has the following goals:

- They are always a full lesson

- They will not contain scandals or sensationalism

- They are never going to be ads in disguise

My personal goals are as follows:

- Produce high quality content

- Answer questions beginners have

- Dive deeply into each topic

If you are able to encourage me to continue, go here. Otherwise, enjoy all of my content for free.

More blog posts by RyanVelez

Practical Openings Approach

This post is for people who need to learn openings, but struggle.

Resigning Strategy

This article is for anyone who wants to understand the strategy of resigning, at both low and high l…

Plateau vs Consistency

How can you become a more consistent player?